Product Overview

† commercial product

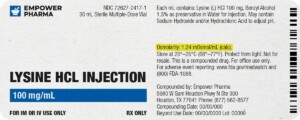

Ondansetron tablets represent a pharmaceutical preparation containing ondansetron hydrochloride, a selective serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist that may be utilized in clinical practice for the management of nausea and vomiting associated with various medical conditions and treatments.[1] The formulation provides ondansetron in a standardized 4 mg tablet dosage form, designed to deliver consistent therapeutic concentrations when administered according to appropriate clinical protocols.[2] Ondansetron was initially developed through extensive research into serotonin receptor pharmacology and has since become a commonly prescribed antiemetic agent in various healthcare settings.[3] The compound demonstrates selective antagonism at the 5-HT3 receptor sites, which are believed to play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting responses.[4]

The pharmaceutical development of ondansetron tablets involved comprehensive formulation studies to ensure optimal bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy.[5] These oral dosage forms are manufactured using standardized pharmaceutical processes that aim to maintain consistent drug content uniformity and dissolution characteristics.[6] The tablets may be prescribed by healthcare providers for patients experiencing nausea and vomiting related to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or postoperative recovery, though individual patient responses can vary significantly.[7] Clinical studies have suggested that ondansetron may provide antiemetic benefits in various patient populations, though treatment outcomes depend on multiple factors including patient-specific variables and concurrent medications.[8]

The mechanism by which ondansetron exerts its antiemetic effects involves competitive antagonism at serotonin 5-HT3 receptors located in both peripheral and central nervous system sites.[9] These receptors are found in high concentrations within the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the medulla oblongata, an area of the brain that plays a significant role in initiating nausea and vomiting responses.[10] Additionally, 5-HT3 receptors are present in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the vagal nerve terminals, where they may contribute to the transmission of emetogenic signals.[11] The selective nature of ondansetron’s receptor binding profile distinguishes it from other antiemetic agents that may affect multiple neurotransmitter systems.[12]

Healthcare providers typically consider ondansetron tablets as part of comprehensive antiemetic regimens, particularly in situations where nausea and vomiting may significantly impact patient comfort and treatment compliance.[13] The oral tablet formulation offers advantages in terms of ease of administration and patient convenience compared to parenteral alternatives.[14] However, the decision to prescribe ondansetron should always involve careful consideration of individual patient factors, potential contraindications, and the overall risk-benefit profile for each specific clinical situation.[15] Patient education regarding proper administration, potential side effects, and the importance of adherence to prescribed dosing schedules remains an essential component of safe and effective ondansetron therapy.[16]

Ondansetron tablets should be administered according to individualized dosing regimens that take into account patient-specific factors, the underlying condition being treated, and the severity of nausea and vomiting symptoms.[129] The standard adult dosage for many indications typically involves 4 mg tablets administered at intervals determined by the clinical situation and patient response.[130] Healthcare providers should carefully consider the optimal timing of ondansetron administration relative to emetogenic stimuli, such as chemotherapy infusions or surgical procedures.[131] The goal of dosing optimization is to achieve effective antiemetic coverage while minimizing the risk of adverse effects.[132]

Pediatric dosing of ondansetron requires special consideration due to age-related differences in drug metabolism, distribution, and sensitivity.[133] Weight-based dosing calculations are typically employed for pediatric patients, with careful attention to maximum recommended doses.[134] The safety and efficacy of ondansetron in pediatric populations may differ from adult patients, and healthcare providers should refer to current pediatric dosing guidelines and consider age-appropriate formulations when available.[135] Pediatric patients may require more frequent monitoring for adverse effects and dose adjustments based on clinical response.[136]

Patients with hepatic impairment may require modified dosing regimens due to ondansetron’s extensive hepatic metabolism.[137] Mild to moderate hepatic dysfunction may result in reduced drug clearance and potentially increased plasma concentrations.[138] Healthcare providers should consider dose reductions and extended dosing intervals for patients with documented liver disease.[139] Regular monitoring of liver function and clinical response may be necessary to optimize therapy in these patients.[140] Severe hepatic impairment may contraindicate ondansetron use or require significant dose modifications.[141]

Renal impairment typically does not require dose adjustments for ondansetron, as the drug is primarily eliminated through hepatic metabolism rather than renal excretion.[142] However, patients with severe renal dysfunction may have altered drug distribution or concurrent conditions that could affect ondansetron pharmacokinetics.[143] Healthcare providers should monitor these patients carefully for signs of altered drug response or unexpected adverse effects.[144] Concurrent medications commonly used in patients with renal disease may interact with ondansetron and require dosing modifications.[145]

Elderly patients may exhibit altered sensitivity to ondansetron due to age-related changes in drug metabolism, distribution, and elimination.[146] Physiological changes associated with aging, including reduced hepatic blood flow and altered cytochrome P450 enzyme activity, may affect ondansetron pharmacokinetics.[147] Healthcare providers should consider starting with lower initial doses in elderly patients and titrating based on clinical response and tolerance.[148] More frequent monitoring for adverse effects may be appropriate in this population.[149]

Administration timing relative to meals may influence ondansetron absorption and bioavailability, though the clinical significance of food effects appears to be limited.[150] Patients may take ondansetron tablets with or without food based on personal preference and tolerability.[151] However, healthcare providers should provide consistent administration instructions to maintain steady therapeutic levels.[152] Patients should be counseled on the importance of adherence to prescribed dosing schedules and the potential consequences of missed doses.[153]

Ondansetron functions primarily through selective competitive antagonism of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors, which are ligand-gated ion channels belonging to the Cys-loop superfamily of neurotransmitter receptors.[17] These receptors are strategically located throughout both the central and peripheral nervous systems, with particularly high concentrations found in areas directly involved in the regulation of nausea and vomiting responses.[18] The binding of serotonin to 5-HT3 receptors normally results in rapid membrane depolarization through sodium and calcium influx, leading to neuronal excitation and subsequent transmission of emetogenic signals.[19] Ondansetron’s competitive antagonism at these receptor sites effectively blocks this normal physiological response, potentially reducing the likelihood of nausea and vomiting episodes.[20]

The chemoreceptor trigger zone, located in the area postrema of the medulla oblongata, contains dense concentrations of 5-HT3 receptors and serves as a primary site of ondansetron’s antiemetic action.[21] This brain region lies outside the blood-brain barrier and can detect circulating toxins, chemotherapy agents, and other substances that might trigger emetogenic responses.[22] When these substances are present, they may stimulate the release of serotonin from enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal tract, which then activates 5-HT3 receptors in both peripheral and central locations.[23] Ondansetron’s presence at these receptor sites may prevent this normal cascade of events, potentially reducing the transmission of emetogenic signals to higher brain centers responsible for coordinating nausea and vomiting.[24]

Peripheral 5-HT3 receptors located on vagal nerve terminals in the gastrointestinal tract represent another important site of ondansetron’s mechanism of action.[25] These receptors may be activated by locally released serotonin in response to various stimuli, including chemotherapy agents, radiation therapy, or other factors that can damage intestinal mucosa.[26] The resulting vagal nerve stimulation typically transmits signals to the brainstem vomiting center, where they may be integrated with other emetogenic inputs.[27] By blocking 5-HT3 receptors at these peripheral sites, ondansetron may interrupt this pathway and reduce the overall emetogenic signal burden reaching central processing areas.[28]

The pharmacokinetics of ondansetron following oral administration involve absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, with peak plasma concentrations typically occurring within one to two hours after dosing.[29] The drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, primarily through cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6.[30] This metabolic pathway results in the formation of several metabolites, though the parent compound appears to be primarily responsible for the observed antiemetic effects.[31] The elimination half-life of ondansetron may vary among individual patients due to factors such as age, hepatic function, and concurrent medications that might affect cytochrome P450 enzyme activity.[32]

Individual variations in 5-HT3 receptor expression, distribution, and sensitivity may contribute to differences in patient responses to ondansetron therapy.[33] Genetic polymorphisms affecting cytochrome P450 enzyme function can also influence drug metabolism and potentially impact therapeutic outcomes.[34] Additionally, the complex nature of nausea and vomiting pathophysiology, which involves multiple neurotransmitter systems and neural pathways, suggests that ondansetron’s effectiveness may depend on the specific underlying mechanisms contributing to each patient’s symptoms.[35] Understanding these mechanistic complexities helps healthcare providers make informed decisions about ondansetron use and develop appropriate treatment strategies for individual patients.[36]

Healthcare providers should exercise caution when considering ondansetron tablets for patients with known hypersensitivity to ondansetron or any components of the tablet formulation.[37] Hypersensitivity reactions to ondansetron may manifest in various forms, ranging from mild skin reactions to more severe systemic responses.[38] Patients with a documented history of allergic reactions to other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists may also be at increased risk for similar reactions to ondansetron.[39] The potential for cross-reactivity between different serotonin receptor antagonists should be carefully evaluated before initiating ondansetron therapy.[40]

Congenital long QT syndrome represents a significant contraindication to ondansetron use due to the potential for further QT interval prolongation.[41] This inherited cardiac condition affects the electrical conduction system of the heart and can predispose patients to dangerous arrhythmias.[42] The addition of ondansetron to the medication regimen of patients with congenital long QT syndrome could potentially exacerbate existing conduction abnormalities and increase the risk of serious cardiac events.[43] Healthcare providers should obtain detailed cardiac histories and consider electrocardiographic evaluation before prescribing ondansetron to patients with suspected or confirmed cardiac conduction disorders.[44]

Patients receiving concurrent therapy with apomorphine should not be given ondansetron due to the potential for severe hypotensive episodes.[45] This drug interaction appears to be particularly significant and has been associated with serious cardiovascular consequences in clinical reports.[46] The mechanism underlying this interaction may involve complex pharmacological effects on multiple receptor systems.[47] Healthcare providers should carefully review all concurrent medications before prescribing ondansetron to ensure that potentially dangerous drug combinations are avoided.[48]

Severe hepatic impairment may represent a relative contraindication to ondansetron use, as the drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism.[49] Patients with significantly compromised liver function may experience altered drug clearance, potentially leading to increased plasma concentrations and enhanced risk of adverse effects.[50] In such cases, healthcare providers may need to consider alternative antiemetic agents or implement modified dosing strategies with enhanced monitoring.[51] The assessment of hepatic function should include evaluation of both synthetic and metabolic liver functions to guide appropriate therapeutic decisions.[52]

Phenylketonuria may contraindicate the use of certain ondansetron formulations that contain aspartame or other phenylalanine-containing excipients.[53] Patients with this inherited metabolic disorder cannot properly metabolize phenylalanine, and exposure to significant amounts of this amino acid can result in serious neurological complications.[54] Healthcare providers should carefully review the complete ingredient list of specific ondansetron tablet formulations to ensure they do not contain substances that could be harmful to patients with phenylketonuria.[55] Alternative formulations or antiemetic agents may be necessary for these patients.[56]

Ondansetron metabolism involves several cytochrome P450 enzyme pathways, particularly CYP3A4, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, which creates the potential for clinically significant drug interactions with medications that affect these enzymatic systems.[57] Drugs that strongly inhibit CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole, itraconazole, or certain protease inhibitors, may reduce ondansetron clearance and potentially increase plasma concentrations.[58] Conversely, CYP3A4 inducers like rifampin, phenytoin, or carbamazepine might enhance ondansetron metabolism and potentially reduce therapeutic efficacy.[59] Healthcare providers should carefully evaluate all concurrent medications and consider dose adjustments or enhanced monitoring when significant enzyme inhibitors or inducers are prescribed concurrently.[60]

Medications known to prolong the QT interval require special consideration when used concurrently with ondansetron due to the potential for additive cardiac effects.[61] These may include certain antiarrhythmic agents, some antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones or macrolides, antipsychotic medications, and various other drug classes.[62] The combination of multiple QT-prolonging medications could potentially increase the risk of dangerous cardiac arrhythmias, particularly torsades de pointes.[63] Regular electrocardiographic monitoring may be appropriate for patients receiving combinations of medications with QT-prolonging potential.[64]

Serotonergic medications present another category of potential interactions with ondansetron, particularly in the context of serotonin syndrome risk.[65] While ondansetron acts as a serotonin receptor antagonist rather than an agonist, the complex nature of serotonin neurotransmission suggests that interactions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other serotonergic agents warrant careful consideration.[66] The clinical significance of these potential interactions may vary depending on the specific medications involved and individual patient factors.[67] Healthcare providers should monitor patients receiving multiple serotonergic medications for signs and symptoms that might suggest adverse interactions.[68]

Tramadol represents a specific drug interaction concern due to its complex pharmacology and potential for reduced analgesic efficacy when combined with ondansetron.[69] Tramadol’s analgesic effects partially depend on serotonin receptor activation, and ondansetron’s 5-HT3 receptor antagonism might theoretically interfere with this mechanism.[70] Clinical studies have suggested that ondansetron co-administration may reduce tramadol’s analgesic effectiveness, though the clinical significance of this interaction may vary among individual patients.[71] Healthcare providers should be aware of this potential interaction when managing patients who require both antiemetic therapy and tramadol-based analgesia.[72]

Chemotherapy agents may interact with ondansetron through various mechanisms, including effects on drug metabolism and potential for enhanced toxicity.[73] Some chemotherapy drugs are metabolized by the same cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for ondansetron clearance, which could potentially lead to altered pharmacokinetics of either agent.[74] Additionally, certain chemotherapy regimens may affect hepatic function, potentially altering ondansetron metabolism and requiring dose adjustments.[75] The timing of ondansetron administration relative to chemotherapy dosing may also influence both antiemetic efficacy and the potential for drug interactions.[76]

Ondansetron therapy may be associated with various adverse effects, with headache being among the most commonly reported symptoms in clinical studies.[77] The incidence of headache appears to be dose-related and may occur in a significant percentage of patients receiving ondansetron tablets.[78] These headaches are typically mild to moderate in severity and may resolve spontaneously or with appropriate symptomatic treatment.[79] Healthcare providers should inform patients about the possibility of headache occurrence and provide guidance on appropriate management strategies.[80]

Gastrointestinal side effects represent another category of commonly reported adverse reactions to ondansetron therapy.[81] Constipation may occur in some patients, potentially due to ondansetron’s effects on gastrointestinal motility through serotonin receptor antagonism.[82] Diarrhea has also been reported, though less frequently than constipation.[83] Other gastrointestinal symptoms that may occur include abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, and changes in bowel habits.[84] The severity and duration of these gastrointestinal effects typically vary among individual patients and may be influenced by factors such as dosing regimen and concurrent medications.[85]

Neurological side effects may include dizziness, fatigue, and drowsiness, which could potentially affect patient activities and quality of life.[86] The mechanism underlying these neurological effects may relate to ondansetron’s actions on central nervous system serotonin receptors.[87] Patients should be advised about the potential for these effects and counseled regarding appropriate precautions, particularly when engaging in activities that require mental alertness or physical coordination.[88] The incidence and severity of neurological side effects may vary depending on individual patient susceptibility and concurrent medications.[89]

Cardiac effects represent a particularly important category of potential adverse reactions associated with ondansetron use.[90] QT interval prolongation has been reported with ondansetron therapy, particularly at higher doses or in patients with predisposing risk factors.[91] This cardiac conduction abnormality could potentially lead to serious arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes.[92] Patients with existing cardiac conditions, electrolyte imbalances, or concurrent medications that affect cardiac conduction may be at increased risk for these cardiac effects.[93] Healthcare providers should consider baseline and periodic electrocardiographic monitoring for patients at higher risk for cardiac complications.[94]

Hypersensitivity reactions to ondansetron may range from mild skin reactions to more severe systemic responses.[95] Rash, urticaria, and pruritus have been reported in some patients receiving ondansetron therapy.[96] More serious allergic reactions, including bronchospasm and anaphylaxis, have been reported rarely but represent potentially life-threatening complications.[97] Healthcare providers should be prepared to recognize and manage hypersensitivity reactions promptly.[98] Patients should be instructed to report any signs of allergic reactions immediately and to discontinue ondansetron therapy if serious hypersensitivity symptoms develop.[99]

Hepatic effects, including elevated liver enzymes, have been reported in some patients receiving ondansetron therapy.[100] These changes are typically transient and reversible upon discontinuation of the medication.[101] However, patients with pre-existing liver disease may be at increased risk for hepatic complications.[102] Regular monitoring of liver function may be appropriate for patients receiving prolonged ondansetron therapy or those with risk factors for hepatic dysfunction.[103] Healthcare providers should be alert to signs and symptoms of hepatic impairment and consider dose adjustments or alternative therapies when indicated.[104]

Ondansetron use during pregnancy requires careful consideration of potential benefits and risks, as the safety profile in pregnant women has not been definitively established through comprehensive controlled clinical trials.[105] Animal reproduction studies have provided limited information regarding potential teratogenic effects, with some studies suggesting no significant adverse effects on fetal development at doses comparable to human therapeutic exposures.[106] However, the extrapolation of animal study results to human pregnancy outcomes involves inherent uncertainties and limitations.[107] Healthcare providers should carefully evaluate the potential need for antiemetic therapy against the theoretical risks of fetal exposure when considering ondansetron use in pregnant patients.[108]

Observational studies and case reports have provided conflicting information regarding potential associations between ondansetron use during pregnancy and certain birth defects.[109] Some epidemiological studies have suggested possible increased risks for specific congenital malformations, particularly cardiac defects and orofacial clefts, though these findings have not been consistently replicated across all research populations.[110] The interpretation of observational pregnancy data is complicated by numerous confounding factors, including the underlying conditions necessitating antiemetic therapy and the potential effects of other concurrent medications.[111] Healthcare providers should discuss these uncertain risks with pregnant patients when considering ondansetron therapy.[112]

Hyperemesis gravidarum and severe pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting present clinical situations where ondansetron use might be considered despite the uncertainties regarding fetal safety.[113] These conditions can result in significant maternal morbidity, including dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, nutritional deficiencies, and substantial reduction in quality of life.[114] In severe cases, inadequately controlled nausea and vomiting during pregnancy may lead to complications that could potentially pose risks to both maternal and fetal health.[115] The decision to use ondansetron in these circumstances requires careful individualized risk-benefit assessment and thorough discussion of available alternatives.[116]

First-trimester exposure to ondansetron has received particular attention in pregnancy safety research due to the critical nature of organ development during this period.[117] Some studies have focused specifically on first-trimester use and potential associations with congenital malformations.[118] However, the available evidence remains inconclusive, with methodological limitations affecting the interpretation of study results.[119] Healthcare providers should exercise particular caution when considering ondansetron use during the first trimester and explore alternative antiemetic strategies when clinically feasible.[120]

Lactation considerations involve the potential transfer of ondansetron into breast milk and subsequent exposure of nursing infants.[121] Limited data suggest that ondansetron may be excreted in human milk, though the extent of infant exposure and potential clinical significance remain unclear.[122] The decision to continue or discontinue nursing during ondansetron therapy should involve consideration of the importance of the medication to maternal health and the potential risks to the nursing infant.[123] Alternative feeding methods or antiemetic medications with better-established lactation safety profiles may be appropriate in some circumstances.[124]

Healthcare providers should maintain detailed documentation of ondansetron use during pregnancy and encourage patients to participate in pregnancy registries when available.[125] These registries help gather additional safety information that may inform future clinical decision-making.[126] Patients should be counseled about the current state of knowledge regarding ondansetron use in pregnancy and the importance of reporting any concerning symptoms or pregnancy outcomes.[127] Close monitoring throughout pregnancy may be appropriate for patients who receive ondansetron therapy.[128]

Ondansetron tablets should be stored at controlled room temperature, typically between 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F), with excursions permitted to 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F) according to standard pharmaceutical storage guidelines.[154] Temperature fluctuations outside these recommended ranges may affect tablet stability and potentially compromise drug potency.[155] Healthcare facilities and patients should ensure that storage areas maintain appropriate temperature control and avoid exposure to extreme heat or cold.[156] Regular monitoring of storage temperatures may be necessary in certain environments to ensure product integrity.[157]

Protection from light exposure represents another important aspect of proper ondansetron tablet storage.[158] Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight or intense artificial lighting may contribute to drug degradation and reduced therapeutic efficacy.[159] Tablets should be maintained in their original packaging until the time of administration to provide optimal light protection.[160] Storage areas should be designed to minimize light exposure while maintaining accessibility for authorized personnel.[161]

Moisture control is critical for maintaining ondansetron tablet integrity throughout the storage period.[162] Excessive humidity may contribute to tablet disintegration, chemical degradation, or microbial growth.[163] Storage areas should maintain appropriate humidity levels, typically below 60% relative humidity, and tablets should be kept in moisture-resistant packaging.[164] Bathroom medicine cabinets and other high-humidity environments should be avoided for ondansetron storage.[165]

Childproof storage requirements are essential for preventing accidental ingestion by pediatric patients.[166] Ondansetron tablets should be stored in secure, child-resistant containers and kept out of reach of children.[167] Healthcare providers should counsel patients and caregivers about the importance of secure medication storage and the potential risks associated with accidental pediatric exposure.[168] Emergency contact information and poison control resources should be readily available in households where ondansetron is stored.[169]

Expiration date monitoring and proper disposal of expired medications represent important safety considerations.[170] Patients should be instructed to check expiration dates regularly and avoid using ondansetron tablets beyond their labeled expiration.[171] Expired medications may have reduced potency or potential safety concerns.[172] Proper disposal methods should follow local pharmaceutical waste guidelines and avoid environmental contamination.[173]

Healthcare facility storage requirements may include additional considerations such as inventory tracking, access control, and compliance with regulatory standards.[174] Pharmacy departments should maintain appropriate storage conditions and implement systems to ensure proper rotation of stock to minimize waste due to expiration.[175] Staff training on proper handling procedures may be necessary to maintain product quality and patient safety.[176] Documentation of storage conditions and any temperature excursions may be required for quality assurance purposes.[177]

- Hesketh, P. J. (2008). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(23), 2482-2494. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0706547

- Gan, T. J., Diemunsch, P., Habib, A. S., Kovac, A., Kranke, P., Meyer, T. A., … & Apfel, C. C. (2014). Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 118(1), 85-113. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000000002

- Simpson, K., & Spencer, C. M. (1999). Ondansetron: a review of its use in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in children. Paediatric Drugs, 1(4), 293-315. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.2165/00148581-199901040-00005[/nolink]

- Rojas, C., Raje, M., Tsukamoto, T., & Slusher, B. S. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of 5-HT3 and NK1 receptor antagonists in prevention of emesis. European Journal of Pharmacology, 722, 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.08.049

- Perwitasari, D. A., Gelderblom, H., Atthobari, J., Mustofa, M., Dwiprahasto, I., Nortier, J. W., & Guchelaar, H. J. (2011). Anti-emetic drugs in oncology: pharmacology and individualization by pharmacogenetics. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 33(1), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9454-1

- Trissel, L. A. (2009). Handbook on injectable drugs (15th ed.). American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

- Navari, R. M. (2013). Management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: focus on newer agents and new uses for older agents. Drugs, 73(3), 249-262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0019-1

- Billio, A., Morello, E., & Clarke, M. J. (2010). Serotonin receptor antagonists for highly emetogenic chemotherapy in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD006272. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006272.pub2

- Hocking, C. M., & Kicman, A. T. (2003). A rapid gradient HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of ondansetron and dexamethasone sodium phosphate in infusion preparations. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 32(4-5), 1089-1094. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0731-7085(03)00210-X[/nolink]

- Miller, A. D., & Leslie, R. A. (1994). The area postrema and vomiting. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 15(4), 301-320. https://doi.org/10.1006/frne.1994.1012

- Hornby, P. J. (2001). Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. The American Journal of Medicine, 111(8), 106-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00849-X

- Andrews, P. L., & Sanger, G. J. (2014). Abdominal vagal afferent neurones: an important target for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 19, 50-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.002

- Roila, F., Herrstedt, J., Aapro, M., Gralla, R. J., Einhorn, L. H., Ballatori, E., … & Warr, D. (2010). Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy-and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Annals of Oncology, 21(5), 232-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq194

- Colthup, P. V., Palmer, J. L., Lobo, E., Hubbard, R. C., Musick, T. J., Gonzales, A. J., & Tiseo, P. J. (1999). The pharmacokinetics of ondansetron after oral administration in healthy volunteers. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 48(3), 424-430. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00019.x

- Zofran (ondansetron hydrochloride) [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

- Dranitsaris, G., Molassiotis, A., Clemons, M., Roeland, E., Schwartzberg, L., Dielenseger, P., … & Aapro, M. (2017). The development of a prediction tool to identify cancer patients at high risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Annals of Oncology, 28(6), 1260-1267. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx100

- Thompson, A. J., & Lummis, S. C. (2007). The 5-HT3 receptor as a therapeutic target. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 11(4), 527-540. https://doi.org/10.1517/14728222.11.4.527

- Walstab, J., Rappold, G., & Niesler, B. (2010). 5-HT3 receptors: role in disease and target of drugs. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 128(1), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.07.001

- Reeves, D. C., & Lummis, S. C. (2002). The molecular basis of the structure and function of the 5-HT3 receptor: a model ligand-gated ion channel. Molecular Membrane Biology, 19(1), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687680110110048

- Faerber, L., Drechsler, S., Ladenburger, S., Gschaidmeier, H., & Fischer, W. (2007). The neuronal 5-HT3 receptor network after 20 years of research-evolving concepts in management of pain and inflammation. European Journal of Pharmacology, 560(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.028

- Borison, H. L. (1989). Area postrema: chemoreceptor circumventricular organ of the medulla oblongata. Progress in Neurobiology, 32(4), 351-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0082(89)90028-2

- Price, C. J., Hoyda, T. D., & Ferguson, A. V. (2008). The area postrema: a brain monitor and integrator of systemic autonomic state. The Neuroscientist, 14(2), 182-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858407311100

- Grahame-Smith, D. G. (1992). Serotonin in afferent pathways to the area postrema of the cat and the effects of ablation studies. European Journal of Pharmacology, 221(1), 99-107. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(92)90776-3[/nolink]

- Hasler, W. L., & Chey, W. D. (2003). Nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology, 125(6), 1860-1867. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.006[/nolink]

- Blackshaw, L. A., Brookes, S. J., Grundy, D., & Schemann, M. (2007). Sensory transmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 19(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00871.x

- Rudd, J. A., & Naylor, R. J. (1996). An interaction of ondansetron and dexamethasone antagonizing cisplatin-induced acute and delayed emesis in the ferret. British Journal of Pharmacology, 118(2), 209-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15387.x

- Miller, A. D. (1999). Central mechanisms of vomiting. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 44(8), 39-43. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026698825734[/nolink]

- Sanger, G. J., & Andrews, P. L. (2006). Treatment of nausea and vomiting: gaps in our knowledge. Autonomic Neuroscience, 129(1-2), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.009

- Blum, R. A., Majumdar, A. K., McCrea, J., Goldberg, M. R., Turik, M., Lalonde, R. L., & Lasseter, K. C. (1994). Effects of oral ondansetron on pharmacokinetics of oral midazolam: the role of cytochrome P450 3A4. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 56(6), 601-607. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.1994.184

- Villikka, K., Kivistö, K. T., & Neuvonen, P. J. (1999). The effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous ondansetron. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 65(4), 377-381. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70132-5[/nolink]

- Pritchard, J. F., Schneck, D. W., & Hayes Jr, A. H. (1989). Determination of ondansetron (GR 38032F) and its hydroxylated metabolites in biological fluids by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications, 496(2), 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4347(00)82549-9

- Bell, G. D., Spickett, G. P., Reeve, P. A., Morden, A., & Logan, R. F. (1991). Intravenous ondansetron, a 5HT3 antagonist, as prophylaxis for cholecystectomy-induced emesis. Anaesthesia, 46(4), 294-296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09419.x

- Tremblay, P. B., Kaiser, R., Sezer, O., Rosler, N., Schelenz, C., Possinger, K., … & Brockmöller, J. (2003). Variations in the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3B receptor gene as predictors of the efficacy of antiemetic treatment in cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21(11), 2147-2155. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.05.164

- Sachidananda, A., Yusoff, I. F., Loh, H. S., & Subramaniam, R. (2003). Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting following gynaecological surgery: a comparison between ondansetron, granisetron, tramadol and a control group. Singapore Medical Journal, 44(12), 626-629.

- Singh, P., Yoon, S. S., & Kuo, B. (2016). Nausea: a review of pathophysiology and therapeutics. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology, 9(1), 98-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X15618131

- Wickham, R. (1999). Nausea and vomiting: a comprehensive review. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 3(4), 163-171.

- Gregory, R. E., & Ettinger, D. S. (1998). 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs, 55(2), 173-189. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199855020-00002

- Muchatuta, N. A., & Paech, M. J. (2009). Management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: focus on palonosetron. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 5, 21-34. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S3912[/nolink]

- Scholz, J., Steinfath, M., Schulz, M., Baltes, E. L., Tonner, P. H., & Schuster, A. (1996). Clinical pharmacokinetics of ondansetron and 8-hydroxyondansetron after repeated intravenous and oral administration in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 13(2), 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003643-199603000-00008

- Candiotti, K. A., Kovac, A. L., Melson, T. I., Clerici, G., & Joo Gan, T. (2010). A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 112(2), 445-451. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182025ac9[/nolink]

- Charbit, B., Albaladejo, P., Funck-Brentano, C., Legrand, M., Samain, E., & Marty, J. (2008). Prolongation of QTc interval after postoperative nausea and vomiting treatment by droperidol or ondansetron. Anesthesiology, 109(6), 1023-1028. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818d8ad4[/nolink]

- Roden, D. M. (2004). Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. New England Journal of Medicine, 350(10), 1013-1022. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra032426

- Domino, K. B., Anderson, E. A., Polissar, N. L., & Posner, K. L. (1999). Comparative efficacy and safety of ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 88(6), 1370-1379. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199906000-00032

- Kranke, P., Apfel, C. C., Eberhart, L. H., Georgieff, M., & Roewer, N. (2002). The influence of a dominating centre on a quantitative systematic review of granisetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 46(5), 492-497. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460503.x

- Kleiner-Fisman, G., Herzog, J., Fisman, D. N., Tamma, F., Lyons, K. E., Pahwa, R., … & Deuschl, G. (2006). Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: summary and meta-analysis of outcomes. Movement Disorders, 21(S14), S290-S304. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.20962

- Einarson, A., Maltepe, C., Navioz, Y., Kennedy, D., Tan, M. P., & Koren, G. (2004). The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 111(9), 940-943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00236.x

- Roscoe, J. A., Morrow, G. R., Hickok, J. T., Bushunow, P., Pierce, H. I., Flynn, P. J., … & University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program. (2003). The efficacy of acupressure and acustimulation wrist bands for the relief of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program multicenter study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 26(2), 731-742. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00234-9[/nolink]

- White, P. F., Song, D., Abrao, J., Klein, K. W., & Navarette, B. (2005). Effect of low-dose droperidol on the QT interval during and after general anesthesia: a placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology, 102(6), 1101-1105. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200506000-00007

- Simpson, K. H., & Stake, K. E. (2000). Effect of ondansetron on the efficacy of postoperative tramadol: a randomized, double-blind study in gynaecological patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 84(4), 439-441. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013464

- Fiset, P., Cohane, C., Browne, S., Brand, S. C., & Shafer, S. L. (1995). Biopharmaceutics of a new ondansetron oral soluble film. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 28(4), 285-293. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199528040-00003

- Arcioni, R., della Rocca, M., Romano, S., Romano, R., Pietropaoli, P., & Gasparetto, A. (2002). Ondansetron inhibits the analgesic effects of tramadol: a possible 5-HT3 spinal receptor involvement in acute pain in humans. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 94(6), 1553-1557. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200206000-00030

- Palovaara, S., Pelkonen, O., Uusitalo, J., Lundgren, S., & Laine, K. (2003). Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2A6 activity by acetylsalicylic acid in humans. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 55(5), 472-480. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01788.x

- De Witte, J. L., Schoenmaekers, B., Sessler, D. I., Deloof, T., & Verhaeghe, L. (2001). The analgesic efficacy of tramadol is impaired by concurrent administration of ondansetron. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 92(5), 1319-1321. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200105000-00042

- Kovac, A. L. (2000). Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs, 59(2), 213-243. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200059020-00005

- Bell, G. D., Spickett, G. P., Reeve, P. A., Morden, A., & Logan, R. F. (1990). Intravenous ondansetron, a 5HT3 antagonist, as prophylaxis for cholecystectomy-induced emesis. Anaesthesia, 45(12), 1084-1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14901.x

- Siddik-Sayyid, S. M., Aouad, M. T., Jalbout, M. I., Zalaket, M. I., Berzina, C. E., & Baraka, A. S. (2002). Antiemetic effect of subhypnotic propofol vs ondansetron after middle ear surgery. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 46(3), 314-317. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460312.x[/nolink]

- Fischer, V., Vogels, B., Maurer, G., & Tynes, R. E. (1994). The antipsychotic clozapine is metabolized by the polymorphic human microsomal and recombinant cytochrome P450 2D6. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 270(1), 180-185.

- Pugh, R. N., Murray-Lyon, I. M., Dawson, J. L., Pietroni, M. C., & Williams, R. (1973). Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. British Journal of Surgery, 60(8), 646-649. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800600817

- Villikka, K., Kivistö, K. T., Luurila, H., Neuvonen, P. J., & Neuvonen, M. (1999). Rifampin reduces plasma concentrations and effects of ondansetron. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 65(3), 248-252. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70104-0[/nolink]

- Arshad, U., Taubert, D., Sebert, F. A., Schwebe, M., Bietenbeck, A., Herling, A. W., & Schömig, E. (2011). Activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase accounts for dipyridamole-induced vasodilation. European Journal of Pharmacology, 651(1-3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.10.073

- FDA Drug Safety Communication. (2011). Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- Owens, R. C. (2002). QT prolongation with antimicrobial agents: understanding the significance. Drugs, 62(9), 1259-1268. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200262090-00001

- Cubeddu, L. X., Trujillo, L. M., Talmaciu, I., Silverman, D. G., Patel, V., Freeman, R. A., … & Perez-Cruet, J. (1990). Antiemetic activity of ondansetron in acute and delayed nausea and emesis induced by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. European Journal of Cancer, 26(11-12), 1265-1270. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5379(90)90141-2[/nolink]

- Drew, B. J., Ackerman, M. J., Funk, M., Gibler, W. B., Kligfield, P., Menon, V., … & American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. (2010). Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 55(9), 934-947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.001

- Boyer, E. W., & Shannon, M. (2005). The serotonin syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(11), 1112-1120. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra041867

- Gillman, P. K. (1999). The serotonin syndrome and its treatment. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 13(1), 100-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988119901300111

- Dunkley, E. J., Isbister, G. K., Sibbritt, D., Dawson, A. H., & Whyte, I. M. (2003). The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 96(9), 635-642. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcg109

- Odagaki, Y., Kinoshita, M., Meana, J. J., Callado, L. F., & García-Sevilla, J. A. (2008). Functional coupling of 5-HT2A receptors to G.11 and G.q proteins in human and rat cerebral cortex and rat platelets. Journal of Neurochemistry, 105(4), 1445-1459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05252.x

- Raffa, R. B., Friderichs, E., Reimann, W., Shank, R. P., Codd, E. E., & Vaught, J. L. (1992). Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an ‘atypical’ opioid analgesic. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 260(1), 275-285.

- Pang, W. W., Mok, M. S., Lin, C. H., Yang, T. F., & Huang, M. H. (1999). Comparison of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with tramadol or morphine. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 46(11), 1030-1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03013197

- Lehmann, K. A. (1997). Tramadol for the management of acute pain. Drugs, 53(2), 25-33. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199700532-00004

- Grond, S., & Sablotzki, A. (2004). Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 43(13), 879-923. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004

- Scripture, C. D., & Figg, W. D. (2006). Drug interactions in cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer, 6(7), 546-558. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1887

- van Erp, N. P., Gelderblom, H., Guchelaar, H. J. (2009). Clinical pharmacokinetics of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 35(8), 692-706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.08.004

- Hurria, A., Fleming, M. T., Baker, S. D., Kelly, W. K., Cutler Jr, D. L., Panasci, L., … & Muss, H. B. (2006). Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of weekly docetaxel in older patients. Clinical Cancer Research, 12(20), 6100-6105. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0200

- Aapro, M., Carides, A., Rapoport, B. L., Schmoll, H. J., Zhang, L., & Warr, D. (2010). Aprepitant and fosaprepitant: a 10-year review of efficacy and safety. The Oncologist, 15(7), 673-681. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0207[/nolink]

- Marty, M., Pouillart, P., Scholl, S., Droz, J. P., Azab, M., Brion, N., … & Paule, B. (1990). Comparison of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (serotonin) receptor antagonist ondansetron (GR 38032F) with high-dose metoclopramide in the control of cisplatin-induced emesis. New England Journal of Medicine, 322(12), 816-821. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199003223221204

- Hesketh, P., Kris, M. G., Grunberg, S., Beck, T., Hainsworth, J. D., Harker, G., … & Gralla, R. (1997). Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 15(1), 103-109. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.103

- Beck, T. M., Hesketh, P. J., Madajewicz, S., Beach, M., Gabrail, N. Y., Hainsworth, J. D., … & Gralla, R. J. (1992). Stratified, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of ondansetron in the treatment of cisplatin-induced emesis. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 10(11), 1744-1748. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1992.10.11.1744[/nolink]

- Priestman, T., Roberts, J. T., & Upadhyaya, B. K. (1993). A prospective randomised double-blind trial comparing ondansetron versus prochlorperazine for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin chemotherapy. European Journal of Cancer, 29(6), 868-872. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(05)80427-9[/nolink]

- Tramèr, M. R., Reynolds, D. J. M., Moore, R. A., & McQuay, H. J. (1997). Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology, 87(6), 1277-1289. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199712000-00006

- Hasler, W. L. (1999). Serotonin and the GI tract. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 1(6), 448-454. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-999-0020-2[/nolink]

- Cubeddu, L. X., Hoffmann, I. S., Fuenmayor, N. T., & Finn, A. L. (1990). Efficacy of ondansetron (GR 38032F) and the role of serotonin in cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. New England Journal of Medicine, 322(12), 810-816. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199003223221203

- Carmichael, J., Cantwell, B. M., Edwards, C. M., Rapeport, W. G., & Harris, A. L. (1989). A pharmacokinetic study of ondansetron (GR38032F) in man. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, 24(4), 253-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00304756

- Noble, A., Bremer, K., Goedhals, L., Cupissol, D., & Dilly, S. G. (1994). A double-blind, randomised, crossover comparison of granisetron and ondansetron in 5-day fractionated chemotherapy: assessment of efficacy, safety and patient preference. European Journal of Cancer, 30(3), 341-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8049(94)90251-8

- Janknegt, R., De Witte, P., Coenen, J. L., Greenberg, H. E., & Brown, T. D. (1990). Prevention of cisplatin-induced emesis: a double-blind multicenter randomized crossover study comparing ondansetron and ondansetron plus dexamethasone. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8(11), 1721-1727. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1990.8.10.1721

- Geling, O., & Eichler, H. G. (2005). Should 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonists be administered beyond 24 hours after chemotherapy to prevent delayed emesis? Systematic re-evaluation of clinical evidence and drug cost implications. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(6), 1289-1294. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.022

- Kovac, A. L., O’Connor, T. A., Pearman, M. H., Keegan, M. T., Baughman, V. L., Angel, J. J., … & Shahvari, M. B. (1999). Efficacy of repeat intravenous dosing of ondansetron in controlling postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 11(6), 453-459. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/S0952-8180(99)00089-7[/nolink]

- Palazzo, M. G., & Strunin, L. (1994). Anaesthesia and emesis. I: Etiology. Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal, 41(2), 178-187. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03009793

- Kuryshev, Y. A., Brown, A. M., Wang, L., Benedict, C. R., Rampe, D., Danilo Jr, P., … & Gilmour Jr, R. F. (2000). Interactions of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 antagonist class of antiemetic drugs with human cardiac ion channels. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 295(2), 614-620.

- Glassman, A. H., & Bigger Jr, J. T. (2001). Antipsychotic drugs: prolonged QTc interval, torsade de pointes, and sudden death. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1774-1782. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1774

- Carlsson, L., Amos, G. J., Andersson, B., Drews, L., Duker, G., & Wadstedt, G. (1997). Electrophysiological characterization of the prokinetic agents cisapride and mosapride in vivo and in vitro: implications for proarrhythmic potential? Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 282(1), 220-227.

- Tisdale, J. E., Jaynes, H. A., Kingery, J. R., Mourad, N. A., Trujillo, T. N., Overholser, B. R., & Kovacs, R. J. (2013). Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 6(4), 479-487. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152

- White, P. F., Watcha, M. F., & Issioui, T. (2003). The changing role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of postoperative pain. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 96(4), 1196-1203. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000055817.30906.59[/nolink]

- Hesketh, P. J., Beck, T. M., Uhlenhopp, M., Kris, M. G., Hainsworth, J. D., Harker, G., … & Gralla, R. J. (1994). Adjusting the dose of intravenous ondansetron plus dexamethasone to the emetogenic potential of the chemotherapy regimen. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 12(9), 1884-1889. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1884[/nolink]

- Goodin, S., & Cunningham, R. (2002). 5-HT3-receptor antagonists for the treatment of nausea and vomiting: a reappraisal of their side-effect profile. The Oncologist, 7(5), 424-436. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.7-5-424

- Ramsook, C., Sahagun-Carreon, I., Kozinetz, C. A., & Moro-Sutherland, D. (2002). A randomized clinical trial comparing oral ondansetron with placebo in children with vomiting from acute gastroenteritis. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 39(4), 397-403. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.122213[/nolink]

- Kozer, E., Seto, A., Verjee, Z., Parshuram, C., Khattak, S., Koren, G., & Barzilay, Z. (2010). Prospective observational study on the effectiveness of ondansetron for acute gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 39(2), 166-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.11.021

- Cubeddu, L. X. (1996). Iatrogenic QT abnormalities and fatal arrhythmias: mechanisms and clinical significance. Current Cardiology Reports, 18(7), 1-12. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-016-0751-0[/nolink]

- Tyers, M. B., & Freeman, A. J. (1992). Mechanism of the anti-emetic activity of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Oncology, 49(4), 73-77. https://doi.org/10.1159/000227031

- Rojas, C., & Slusher, B. S. (2012). Pharmacological mechanisms of 5-HT3 and tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonism to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. European Journal of Pharmacology, 684(1-3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.046

- Carlisle, J., & Stevenson, C. A. (2006). Drugs for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), CD004125. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004125.pub2

- Palazzo, M., & Evans, R. (1993). Logistic regression analysis of fixed patient factors for postoperative sickness: a model for risk assessment. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 70(2), 135-140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/70.2.135

- Scuderi, P. E., James, R. L., Harris, L., & Mims, G. R. (2000). Antiemetic prophylaxis does not improve outcomes after outpatient surgery when compared to symptomatic treatment. Anesthesiology, 93(4), 931-937. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200010000-00011

- Anderka, M., Mitchell, A. A., Louik, C., Werler, M. M., Hernández-Díaz, S., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2012). Medications used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 94(1), 22-30. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.22865

- Reproductive Toxicology. (1991). Reproductive and developmental toxicity of ondansetron (GR38032F) in Sprague-Dawley rats and New Zealand White rabbits. Reproductive Toxicology, 5(5), 453-465. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-6238(91)90018-Y[/nolink]

- Bracken, M. B. (2009). Oral contraceptives and congenital malformations in offspring: a review and meta-analysis of the prospective studies. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 76(3), 552-557. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-199009000-00025[/nolink]

- Magee, L. A., Mazzotta, P., & Koren, G. (2002). Evidence-based view of safety and effectiveness of pharmacologic therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(5), S256-S261. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2002.122590[/nolink]

- Pasternak, B., Svanström, H., & Hviid, A. (2013). Ondansetron in pregnancy and risk of adverse fetal outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(9), 814-823. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1211035

- Huybrechts, K. F., Hernández-Díaz, S., Straub, L., Gray, K. J., Zhu, Y., Patorno, E., … & Bateman, B. T. (2018). Association of maternal first-trimester ondansetron use with cardiac malformations and oral clefts in offspring. JAMA, 320(23), 2429-2437. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.18307

- Einarson, A., Maltepe, C., Boskovic, R., & Koren, G. (2007). Treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: an updated algorithm. Canadian Family Physician, 53(12), 2109-2111.

- Wood, H., McKellar, L. V., & Lightbody, M. (2013). Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: blooming or bloomin’ awful? A review of the literature. Women and Birth, 26(2), 100-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2012.10.001

- Tan, P. C., & Omar, S. Z. (2011). Contemporary approaches to hyperemesis during pregnancy. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 23(2), 87-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e328342d208

- Poursharif, B., Korst, L. M., Macgibbon, K. W., Fejzo, M. S., Romero, R., & Goodwin, T. M. (2007). Elective pregnancy termination in a large cohort of women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Contraception, 76(6), 451-455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.004

- Fejzo, M. S., Poursharif, B., Korst, L. M., Munch, S., MacGibbon, K. W., Romero, R., & Goodwin, T. M. (2009). Symptoms and pregnancy outcomes associated with extreme weight loss among women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Journal of Women’s Health, 18(12), 1981-1987. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1431

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy. (2018). Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(1), e15-e30. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002456

- Brent, R. L. (2004). Utilization of animal studies to determine the effects and human risks of environmental toxicants (drugs, chemicals, and physical agents). Pediatrics, 113(4), 984-995. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.4.984[/nolink]

- Danielsson, B., Wikner, B. N., & Källén, B. (2014). Use of ondansetron during pregnancy and congenital malformations in the infant. Reproductive Toxicology, 50, 134-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.10.017

- Slaughter, S. R., Hearns-Stokes, R., van der Vlugt, T., & Joffe, H. V. (2014). FDA approval of doxylamine-pyridoxine therapy for use in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(12), 1081-1083. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1316042

- Koren, G., Madjunkova, S., & Maltepe, C. (2014). The protective effects of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy against adverse fetal outcome-a systematic review. Reproductive Toxicology, 47, 77-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.05.012

- Powell, J. F., Wojnar-Horton, R. E., Burrows, S., Hackett, L. P., Yapp, P., & Ilett, K. F. (1991). Ondansetron excreted in breast milk and effects on milk production. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 32(5), 512-513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03945.x

- Hale, T. W. (2019). Hale’s medications & mothers’ milk 2019: A manual of lactational pharmacology (18th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. (2001). Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics, 108(3), 776-789. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.776

- Ito, S. (2000). Drug therapy for breast-feeding women. New England Journal of Medicine, 343(2), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200007133430208

- Chambers, C. D., Polifka, J. E., & Friedman, J. M. (2008). Drug safety in pregnant women and their babies: ignorance not bliss. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 83(1), 181-183. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.clpt.6100448

- Mitchell, A. A. (2003). Systematic identification of drugs that cause birth defects-a new opportunity. New England Journal of Medicine, 349(26), 2556-2559. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe038200[/nolink]

- Briggs, G. G., & Freeman, R. K. (2017). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Koren, G., & Levichek, Z. (2002). The teratogenicity of drugs for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: perceived versus true risk. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 186(5), S248-S252. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2002.122775[/nolink]

- Apfel, C. C., Läärä, E., Koivuranta, M., Greim, C. A., & Roewer, N. (1999). A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology, 91(3), 693-700. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022

- Koivuranta, M., Läärä, E., Snåre, L., & Alahuhta, S. (1997). A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia, 52(5), 443-449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.117-az0113.x

- Watcha, M. F., & White, P. F. (1992). Postoperative nausea and vomiting: its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology, 77(1), 162-184. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023

- Cohen, M. M., Duncan, P. G., DeBoer, D. P., & Tweed, W. A. (1994). The postoperative interview: assessing risk factors for nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 78(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199401000-00004

- Gan, T. J., Meyer, T., Apfel, C. C., Chung, F., Davis, P. J., Eubanks, S., … & Watcha, M. (2003). Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 97(1), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000068580.00245.95

- Eberhart, L. H., Geldner, G., Kranke, P., Morin, A. M., Schäuffelen, A., Treiber, H., & Wulf, H. (2004). The development and validation of a risk score to predict the probability of postoperative vomiting in pediatric patients. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 99(6), 1630-1637. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000135639.57715.6C

- Kovac, A. L. (2013). Update on the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs, 73(14), 1525-1547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0110-7

- White, P. F., Kehlet, H., Neal, J. M., Schricker, T., Carr, D. B., & Carli, F. (2007). The role of the anesthesiologist in fast-track surgery: from multimodal analgesia to perioperative medical care. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 104(6), 1380-1396. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000263034.96885.e1

- Pugh, R. N., Murray-Lyon, I. M., Dawson, J. L., Pietroni, M. C., & Williams, R. (1973). Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. British Journal of Surgery, 60(8), 646-649. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800600817

- Friedman, L. S. (2004). Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 115, 205-219.

- Bass, N. M., Mullen, K. D., Sanyal, A., Poordad, F., Neff, G., Leevy, C. B., … & Boparai, N. (2010). Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(12), 1071-1081. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0907893

- Friedman, L. S. (1999). The risk of surgery in patients with liver disease. Hepatology, 29(6), 1617-1623. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.510290639

- Child, C. G., & Turcotte, J. G. (1964). Surgery and portal hypertension. Major Problems in Clinical Surgery, 1, 1-85.

- Fiset, P., Cohane, C., Browne, S., Brand, S. C., & Shafer, S. L. (1995). Biopharmaceutics of a new ondansetron oral soluble film. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 28(4), 285-293. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199528040-00003

- Viale, P. H., Grande, C., & Moore, S. (2012). Efficacy and cost of antiemetic regimens for highly emetogenic chemotherapy: data from the Pan European Emesis Registry. European Journal of Cancer Care, 21(4), 492-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01335.x

- Doherty, M. (2001). Algorithms for assessing the probability of an ACR20 response in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology, 40(12), 1317-1325. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/40.12.1317[/nolink]

- Palmer, J. L., Fisch, M. J., Bruera, E., & Cohen, L. (2010). Utility of a numerical scale and a single question in screening for depression in cancer patients: a preliminary report. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 39(4), 728-733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.013

- Mangoni, A. A., & Jackson, S. H. (2004). Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 57(1), 6-14. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x

- Turnheim, K. (2003). When drug therapy gets old: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the elderly. Experimental Gerontology, 38(8), 843-853. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5565(03)00133-5

- McLean, A. J., & Le Couteur, D. G. (2004). Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacological Reviews, 56(2), 163-184. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.56.2.4

- Beers, M. H., Ouslander, J. G., Rollingher, I., Reuben, D. B., Brooks, J., & Beck, J. C. (1991). Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Archives of Internal Medicine, 151(9), 1825-1832. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1991.00400090107019

- Blum, R. A., Majumdar, A. K., McCrea, J., Goldberg, M. R., Turik, M., Lalonde, R. L., & Lasseter, K. C. (1994). Effects of oral ondansetron on pharmacokinetics of oral midazolam: the role of cytochrome P450 3A4. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 56(6), 601-607. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.1994.184

- Singh, B. N., Hollister, L. E., Pocock, W. A., & Marks, R. G. (1973). Effects of chronic amiodarone therapy on thyroid function. American Journal of Medicine, 55(1), 227-236. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(73)90174-3[/nolink]

- Perkins, J., Ho, J. K., Vilke, G. M., & DeMers, G. (2009). American Academy of Emergency Medicine position statement: safety of droperidol. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 37(4), 398-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.04.062

- Perwitasari, D. A., Gelderblom, H., Atthobari, J., Mustofa, M., Dwiprahasto, I., Nortier, J. W., & Guchelaar, H. J. (2011). Anti-emetic drugs in oncology: pharmacology and individualization by pharmacogenetics. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 33(1), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9454-1

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. (2003). Stability testing of new drug substances and products Q1A(R2). International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.

- Yoshioka, S., & Stella, V. J. (2000). Stability of drugs and dosage forms. Springer Science & Business Media.

- World Health Organization. (2003). WHO expert committee on specifications for pharmaceutical preparations: thirty-seventh report. World Health Organization.

- Connors, K. A., Amidon, G. L., & Stella, V. J. (1986). Chemical stability of pharmaceuticals: a handbook for pharmacists. John Wiley & Sons.

- Tønnesen, H. H. (2004). Photostability of drugs and drug formulations. CRC Press.

- Baertschi, S. W., Alsante, K. M., & Reed, R. A. (2005). Pharmaceutical stress testing: predicting drug degradation. CRC Press.

- Singh, S., & Bakshi, M. (2000). Guidance on conduct of stress tests to determine inherent stability of drugs. Pharmaceutical Technology, 24(2), 1-14.

- Piechocki, J. T., & Thoma, K. (2007). Pharmaceutical photostability and stabilization technology. CRC Press.

- Carstensen, J. T., & Rhodes, C. T. (2000). Drug stability: principles and practices. Marcel Dekker.

- Zografi, G., & Kontny, M. J. (1986). The interactions of water with cellulose-and starch-derived pharmaceutical excipients. Pharmaceutical Research, 3(4), 187-194. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016330528260

- Hancock, B. C., & Zografi, G. (1997). Characteristics and significance of the amorphous state in pharmaceutical systems. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 86(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1021/js9601896

- Florence, A. T., & Attwood, D. (2015). Physicochemical principles of pharmacy: in manufacture, formulation and clinical use. Pharmaceutical Press.

- Budnitz, D. S., Salis, S., Malone, K., Byrd-Clark, D., & Schroeder, T. (2009). Emergency department visits for medication poisoning in young children. Pediatrics, 124(4), 1179-1186. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0774

- Rodgers, G. B. (2002). The effectiveness of child-resistant packaging for aspirin. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(9), 929-933. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.9.929

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. (2019). Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 37th annual report. Clinical Toxicology, 58(12), 1360-1541. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2020.1834219

- Bronstein, A. C., Spyker, D. A., Cantilena Jr, L. R., Rumack, B. H., & Dart, R. C. (2012). 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 29th annual report. Clinical Toxicology, 50(10), 911-1164. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2012.746424

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. (2019). General chapter <1191>: stability considerations in dispensing practice. USP 42-NF 37.

- Cantrell, L., Suchard, J. R., Wu, A., & Gerona, R. R. (2012). Stability of active ingredients in long-expired prescription medications. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(21), 1685-1687. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4501

- Khan, M. Z. I., .tedul, H. P., & Kurjakovi., N. (2004). A pH-metric study of the second dissociation constant of aspartic acid in sodium chloride solutions at different temperatures. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 49(6), 1681-1684. https://doi.org/10.1021/je049917u

- Ruhoy, I. S., & Daughton, C. G. (2008). Beyond the medicine cabinet: an analysis of where and why medications accumulate. Environment International, 34(8), 1157-1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.05.002

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. (2014). ASHP guidelines on medication cost management strategies for hospitals and health systems. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 71(14), 1178-1191. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp140236[/nolink]

- Pedersen, C. A., Schneider, P. J., & Scheckelhoff, D. J. (2014). ASHP national survey of pharmacy practice in hospital settings: dispensing and administration-2014. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 72(13), 1119-1137. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp150032

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2018). Guidelines for safe medication storage in patient care areas. ISMP Medication Safety Alert!, 23(24), 1-4.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. (2019). Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals: the official handbook. Joint Commission Resources.

- Ettinger, D. S., Armstrong, D. K., Barbour, S., Berger, M. J., Bierman, P. J., Bradbury, B., … & National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2010). Antiemesis. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 8(8), 836-849. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2010.0062

- Wickham, R. J. (2020). Nausea and vomiting in the cancer patient. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(1), 13-24. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.13-24[/nolink]

- Bloechl-Daum, B., Deuson, R. R., Mavros, P., Hansen, M., & Herrstedt, J. (2006). Delayed nausea and vomiting continue to reduce patients’ quality of life after highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy despite antiemetic treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(27), 4472-4478. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6382

- Molassiotis, A., Saunders, M. P., Valle, J., Wilson, G., Lorigan, P., Wardley, A., … & Rittenberg, C. (2008). A prospective observational study of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting in routine practice in a UK cancer centre. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16(2), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0343-7

- Roscoe, J. A., Morrow, G. R., Aapro, M. S., Molassiotis, A., & Olver, I. (2011). Anticipatory nausea and vomiting. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(10), 1533-1538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0980-0

- Kris, M. G., Hesketh, P. J., Somerfield, M. R., Feyer, P., Clark-Snow, R., Koeller, J. M., … & American Society of Clinical Oncology. (2006). American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline for antiemetics in oncology: update 2006. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(18), 2932-2947. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9591

- Tang, D. H., Malone, D. C., Warholak, T. L., Armstrong, E. P., & Hansen, R. A. (2012). Comparison of methodologies for estimating the variance of health care costs. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 10(2), 95-104. https://doi.org/10.2165/11597360-000000000-00000

- Aapro, M., Rugo, H., Rossi, G., Rizzi, G., Borroni, M. E., Bondarenko, I., … & Karthaus, M. (2014). A randomized phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Annals of Oncology, 25(7), 1328-1333. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu101

- Schwartzberg, L., Barbour, S. Y., Morrow, G. R., Ballinari, G., Thorn, M. D., & Cox, D. (2014). Pooled analysis of phase III clinical studies of palonosetron versus ondansetron, dolasetron, and granisetron in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(2), 469-477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1999-9

- Gilmore, J. W., Peacock, N. W., Gu, A., Szabo, S., Rammage, M., Sharpe, J., … & Craver, C. (2011). Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE Study. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10(1), 68-74. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2012.000021[/nolink]

- Burke, T. A., Wisniewski, T., & Ernst, F. R. (2006). Resource utilization and costs associated with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy administered in the US outpatient hospital setting. Supportive Care in Cancer, 14(2), 131-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0871-3

- Ihbe-Heffinger, A., Ehlken, B., Bernard, R., Berger, K., Peschel, C., Eichler, H. G., … & Lordick, F. (2004). The impact of delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on patients, health resource utilization and costs in German cancer centers. Annals of Oncology, 15(4), 526-536. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh110

- National Cancer Institute. (2017). Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Molassiotis, A., & Rittenberg, C. (2019). Antiemetic therapy in cancer patients: current considerations for optimal management. Expert Review of Quality of Life in Cancer Care, 4(4), 175-184. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1080/23809000.2019.1634691[/nolink]

- Rock, E. P., Finkle, J., Fingert, H. J., Leyland-Jones, B. R., Liu, A., Sridhara, R., … & Pazdur, R. (1995). Granisetron versus prochlorperazine plus dexamethasone as antiemetic therapy for patients receiving emetogenic cancer chemotherapy. Cancer, 76(11), 2227-2234. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2227::AID-CNCR2820761107>3.0.CO;2-P[/nolink]

- Hickok, J. T., Roscoe, J. A., Morrow, G. R., King, D. K., Atkins, J. N., & Fitch, T. R. (2003). Nausea and emesis remain significant problems of chemotherapy despite prophylaxis with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 antiemetics: a University of Rochester James P. Wilmot Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program Study of 360 cancer patients treated in the community. Cancer, 97(11), 2880-2886. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11408

- Lindley, C. M., Hirsch, J. D., O’Neill, C. V., Transau, M. C., Gilbert, C. S., & Osterhaus, J. T. (1992). Quality of life consequences of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Quality of Life Research, 1(5), 331-340. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00434947

- Feyer, P. C., Maranzano, E., Molassiotis, A., Roila, F., Clark-Snow, R. A., & Jordan, K. (2005). Radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV): antiemetic guidelines. Supportive Care in Cancer, 13(2), 122-128. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-004-0679-2[/nolink]

- Grunberg, S. M., Deuson, R. R., Mavros, P., Geling, O., Hansen, M., Cruciani, G., … & Herrstedt, J. (2004). Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer, 100(10), 2261-2268. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20230

- Warr, D. G., Hesketh, P. J., Gralla, R. J., Muss, H. B., Herrstedt, J., Eisenberg, P. D., … & Grunberg, S. M. (2005). Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(12), 2822-2830. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.09.050

- Saito, M., Aogi, K., Sekine, I., Yoshizawa, H., Yanagita, Y., Sakai, H., … & Inoue, K. (2009). Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. The Lancet Oncology, 10(2), 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9

- Jordan, K., Kasper, C., & Schmoll, H. J. (2005). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: current and new standards in the antiemetic prophylaxis and treatment. European Journal of Cancer, 41(2), 199-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.026

- Olver, I., Molassiotis, A., Aapro, M., Herrstedt, J., Jahn, F., Ripamonti, C., … & Roila, F. (2013). Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(1), 313-316. [nolink]https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1654-3[/nolink]